Formulation Science in Resource-Constrained Environments: Where Limits Become the Laboratory

Formulation science is often imagined as a discipline of abundance—high-purity solvents, precisely engineered excipients, uninterrupted power, sterile suites, and instruments that report every fluctuation in viscosity or particle size as a neat curve on a screen. Yet much of the world does not formulate under those conditions. Across emerging manufacturing hubs, remote field stations, public hospitals, disaster-relief supply chains, and small industrial clusters, scientists routinely face the opposite reality: intermittent electricity, constrained cold-chain logistics, variable water quality, uncertain raw-material provenance, limited analytical bandwidth, and a constant pressure to reduce cost without compromising performance. In these environments, innovation is not a luxury. It is a survival mechanism—and formulation becomes less about perfect inputs and more about designing resilience into matter itself.

Resource-constrained formulation is not “lower-quality science.” It is, in many ways, a more demanding version of the same discipline because the system must tolerate uncertainty. A cream that separates when the ambient temperature rises is not merely inconvenient; it becomes unusable in a rural clinic. A pesticide formulation that clogs nozzles due to small changes in water hardness can erase an entire spraying window. A tablet that absorbs moisture during monsoon transport can silently fail before it ever reaches a patient. Constraints reveal the true job of a formulation scientist: to engineer stability, reproducibility, and usability into a product even when the world refuses to behave like a controlled laboratory.

The Physics of “Not Enough”: What Constraints Really Mean

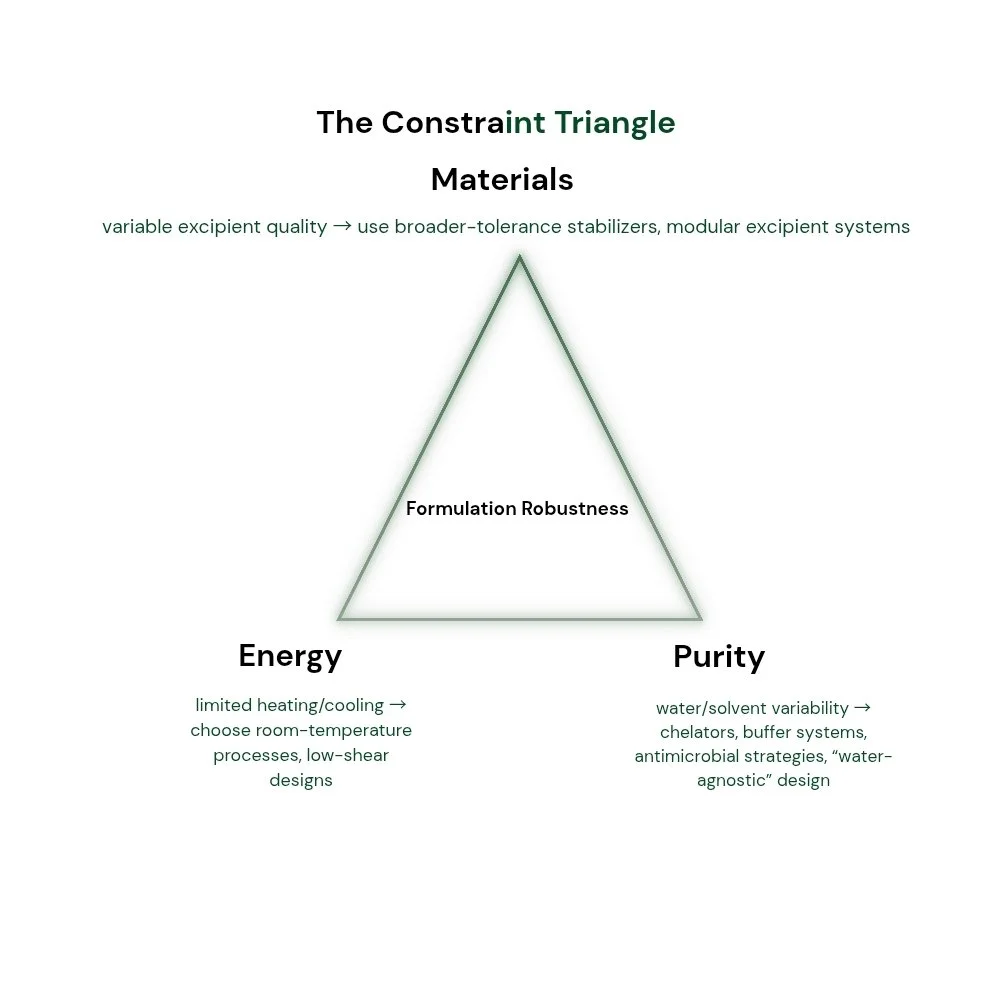

When materials, energy, and purity are limited, formulation problems rarely present as a single failure mode. They emerge as cascades. A slightly impure solvent changes solubility. That altered solubility shifts nucleation behavior. Nucleation changes particle size distribution. Particle size changes rheology. Rheology alters fill-weight variability. Fill-weight variability affects dosage uniformity or application rate. In a resource-rich setting, each step might be buffered by process controls and redundant analytics. Under constraint, the cascade is shorter, faster, and more punishing.

Material limitations appear in many forms: excipients that vary between suppliers, surfactants with inconsistent active content, polymers with drifting molecular weight distributions, and pigments or mineral fillers whose trace ions reshape interfacial behavior. Energy constraints translate into fewer temperature ramps, fewer long mixing cycles, and reduced ability to hold narrow process windows. Purity constraints—especially in water—introduce ionic strength, hardness, microbial load, and dissolved organics that can destabilize emulsions, catalyze degradation, or disrupt dispersion.

The core challenge is not merely “making it work once.” It is making it work repeatedly across variability that cannot be fully eliminated. This is why resource-constrained formulation is best treated as a design philosophy: choose mechanisms that are robust by nature, not fragile mechanisms that require constant correction.

Formulation Under Uncertainty: The Hidden Variables That Matter Most

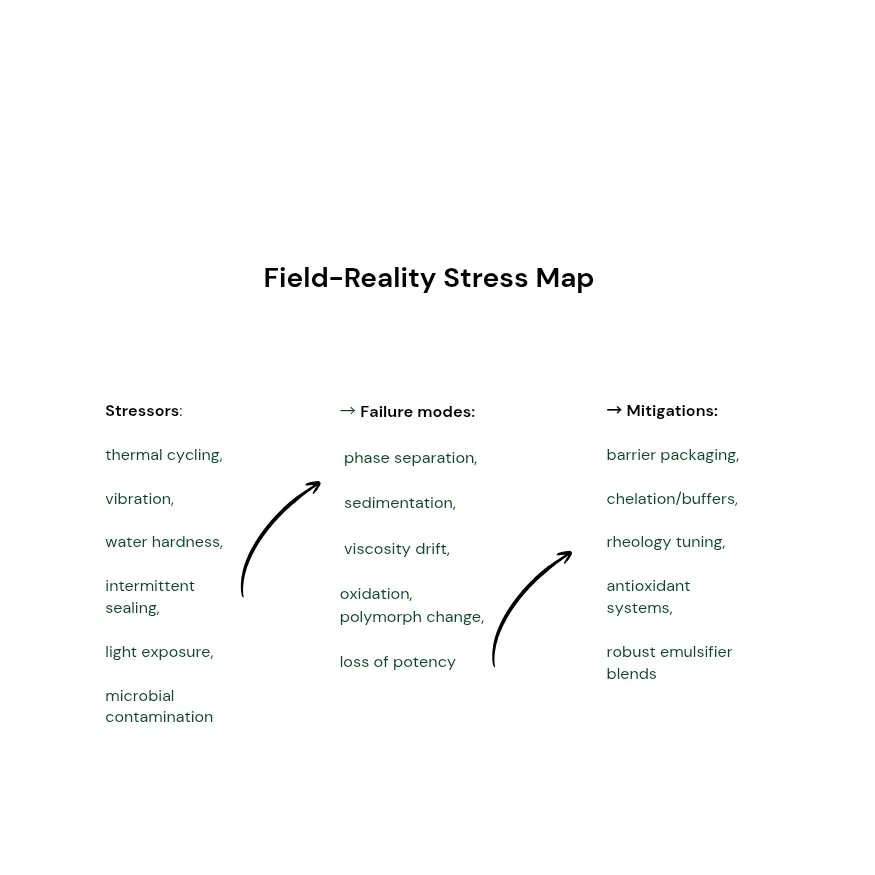

In constrained environments, formulation performance is often dominated by variables that are treated as “background noise” elsewhere. Water hardness can invert the behavior of surfactants. Trace metals can accelerate oxidation in active ingredients. Packaging permeability can become the true stability driver rather than the formula itself. Even mixing order—often considered a procedural detail—can determine whether a dispersion is stable or destined to aggregate.

One of the most underestimated variables is temperature variability during distribution. Products that never see a stability chamber may still face repeated thermal cycling: hot daytime transport, cool nights, warehouse heat, or cold exposure at altitude. These cycles can trigger polymorphic transitions, phase separation, viscosity drift, and gas solubility changes. The formulation scientist’s task becomes analogous to designing a bridge in an earthquake zone: the product must not only stand under ideal conditions but flex without breaking under repeated stress.

A second underestimated variable is microbial pressure. Limited sterility infrastructure and warm storage conditions increase the biological burden in water-based formulations. Preservatives are not a “checkbox ingredient”; they are a system that must be compatible with surfactants, polymers, pH, packaging interactions, and user handling. Preservative efficacy also becomes a function of how the product is used—multi-dose containers, repeated exposure to ambient air, or dilution at the point of use.

A third variable is measurement scarcity. When advanced analytics are unavailable, the scientist must learn to extract maximum information from minimal tests—simple viscosity measurements, sedimentation observation, pH drift, conductivity, and accelerated stress conditions that mimic real transport rather than idealized protocols. In these settings, formulation success depends as much on experimental design as it does on chemistry.

Designing for Robustness: Strategies That Work When the World Is Messy

1) “Water-Agnostic” Formulation Thinking

Water is the most common solvent and the most common source of hidden failure. In resource-limited settings, water may be hard, mineral-rich, microbially contaminated, or inconsistent day to day. Water-agnostic design does not assume purity; it assumes variability and builds tolerance through buffering capacity, chelation where appropriate, controlled ionic strength, and emulsifier systems that do not collapse under moderate hardness shifts.

For example, emulsions can be designed with interfacial films that are less sensitive to salt screening, using combinations of surfactants and polymers that create steric stabilization rather than relying purely on electrostatic repulsion. In dispersions, the choice of dispersant can be framed as a “robustness lever” rather than a performance enhancer. The goal becomes to prevent catastrophic aggregation even if the water chemistry changes.

2) Stability as a Structural Feature, Not a Post-Test Outcome

In high-resource environments, stability can be treated as something you evaluate after optimizing performance. Under constraint, stability must be architected from the beginning. This includes selecting rheology modifiers that resist temperature cycling, choosing crystal forms that are less prone to transformation, and using packaging that acts as a stability partner rather than a passive container.

A key mindset shift is to treat packaging–formulation interactions as first-class science. A highly optimized formulation can fail in a permeable container through solvent loss, oxygen ingress, or moisture uptake. Conversely, a slightly less “perfect” formulation can become reliable if paired with barrier packaging and practical dispensing design. In constrained distribution networks, packaging often determines whether a product survives.

3) Process Simplification Without Performance Collapse

Energy constraints push teams toward room-temperature processing, shorter cycles, and less reliance on tight thermal control. The risk is that simplified processes create hidden variability. The solution is not to “do less science,” but to choose formulation mechanisms that are less process-sensitive.

A robust formulation is one that does not require a narrow shear profile to prevent agglomeration, does not need a precise cooling curve to avoid undesired crystallization, and does not depend on fragile pH targets that drift with CO₂ absorption. This is why in constrained settings, formulations that are “forgiving” to mixing order and process variation often outperform more elegant but delicate systems.

4) Multi-Functionality: One Ingredient, Several Jobs

When materials are limited, multi-functional excipients become strategic. An ingredient that provides both stabilization and viscosity control can reduce the number of dependencies in the system. Fewer ingredients mean fewer supply-chain vulnerabilities, fewer compatibility risks, and simpler quality control. The formulation becomes not only a chemical design but also a logistical design.

5) Stress Testing That Mirrors Reality

Traditional accelerated stability studies can miss the stress patterns that matter most in constrained environments. The real world delivers repeated thermal cycles, vibration, freeze-thaw events, and intermittent exposure to air and light. Designing stress protocols that reflect these patterns produces data that is more predictive and less cosmetic. A formulation that survives “perfect” stability conditions but fails in field-like cycling is not stable—it is merely well-behaved in a controlled room.

Case Examples Across Industries

Pharmaceuticals: The Cold-Chain Problem That Formulation Must Solve

Many therapies assume stable refrigeration from factory to patient. In reality, cold-chain interruptions are common in remote distribution. A formulation designed for thermal resilience—through stabilizing excipients, optimized glass transition behavior in solids, or protective microenvironments around sensitive molecules—can reduce dependence on perfect logistics. Even when refrigeration exists, the formulation that tolerates short excursions is the one that actually reaches the patient intact.

Agrochemicals: Performance Depends on the Farmer’s Water

In crop protection, products are often diluted at the point of use with whatever water is available—hard, turbid, mineral-rich, or inconsistent. Formulations that remain dispersible, resist nozzle clogging, and maintain droplet behavior across variable water chemistry are the ones that succeed. Here, the formulation must be “field-compatible,” not merely “lab-optimized.” Robust dispersants, controlled particle size distributions, and water-tolerant surfactant systems become the difference between adoption and abandonment.

Consumer Products and Hygiene: The Hidden Enemy Is Microbial Drift

Soaps, creams, and gels face repeated user contact and warm storage. Preservative systems must function not only in theory but in daily handling reality. In constrained settings, a product may be used beyond its intended period or stored in open environments. Formulation strategies that maintain antimicrobial efficacy without harshness, while also resisting viscosity collapse and phase separation, become essential.

Industrial Formulations: When Purity Is a Luxury

Lubricants, coatings, and construction chemicals often face raw-material variability and storage stress. A formulation designed with broad tolerance to filler variability, moisture content changes, and temperature fluctuations can reduce field failures and rework costs. In many industries, the most expensive failure is not the ingredient cost—it is the downtime, the rejection, and the reputational loss.

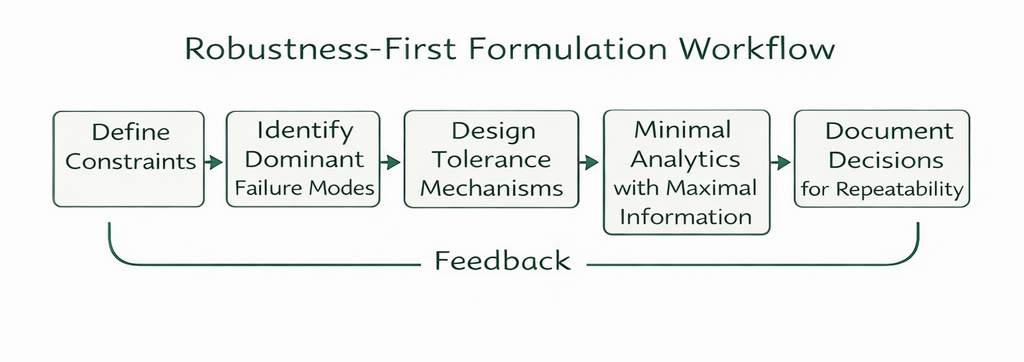

The Most Valuable Skill in Constrained Formulation: Decision Quality

Resource-constrained environments punish poor decisions more than they reward clever chemistry. The best teams do not rely on heroic troubleshooting. They build systems that prevent problems from emerging, and they document why each choice was made. This is where formulation science begins to resemble engineering ethics: decisions must be reproducible, explainable, and transferable across teams.

However, decision quality is threatened by one persistent problem—fragmented experimental memory. Data lives in scattered notebooks, spreadsheets, chat threads, and individual recollections. When a project is paused, the rationale disappears. When a team member leaves, the logic leaves with them. The result is repeated experiments, repeated mistakes, and repeated months lost to rediscovering what the organization already learned.

In resource-constrained settings, repetition is not merely inefficient—it is unaffordable.

Where ChemCopilot Fits: Turning Constraints Into Structured Intelligence

ChemCopilot’s role in this landscape is not to “replace” formulation scientists. It is to protect their time, preserve their learning, and increase the probability that each experiment produces transferable insight.

1) ChemCopilot as a Scientific Memory Layer

In constrained labs, experiments are often designed around what is feasible rather than what is ideal. ChemCopilot can help capture formulation intent, experimental conditions, observed outcomes, and decision rationale in a structured way—so knowledge accumulates instead of evaporating. This matters because robustness emerges from patterns across trials: which surfactant systems tolerate hardness, which polymers resist thermal cycling, which mixing orders reduce aggregation, which packaging interactions cause drift.

A formulation team that remembers precisely is a team that advances quickly—even with limited equipment.

2) ChemCopilot as an Experiment Design Partner Under Constraints

When resources are limited, experimental design must be efficient. ChemCopilot can support smarter screening by helping teams define dominant variables, prioritize risk factors, and create compact test matrices that still reveal mechanism. The objective is not “more experiments,” but more information per experiment—especially when materials are scarce or expensive.

3) ChemCopilot as a Documentation Engine for Compliance and Transferability

Many constrained environments still operate under strict regulatory or customer expectations. ChemCopilot can help translate iterative lab work into coherent documentation: what changed, why it changed, what risks were addressed, and what evidence supports stability. This is particularly valuable when scaling from a small lab to pilot production, where missing context can create costly manufacturing surprises.

4) ChemCopilot as a Failure-Mode Translator

In real formulation work, failures are often ambiguous: a slight viscosity drift, an unexpected sediment layer, a faint odor change, a slow potency loss. ChemCopilot can help teams connect observations to plausible mechanisms—oxidation, hydrolysis, incompatibility, microbial growth, phase inversion, crystallization—so troubleshooting becomes hypothesis-driven rather than guess-driven.

This is how constrained labs gain leverage: by making uncertainty navigable.

The Deeper Point: Constraint Is Not the Opposite of Innovation

There is a quiet truth in formulation science: abundance can hide weak design. If a product only works when the inputs are pristine and the process is perfect, it is not truly robust—it is merely protected. Resource-constrained environments remove that protection and expose what matters. They force the formulation scientist to build products that are tolerant, stable, and usable across real-world variability.

This is why some of the most meaningful formulation advances emerge from constrained settings. They are not flashy. They are durable. They reduce dependence on fragile infrastructure. They respect the complexity of the world instead of denying it.

Formulation science, at its best, is the art of making matter behave reliably. Under constraint, that art becomes more honest—and more essential. And with platforms like ChemCopilot that preserve learning, sharpen decisions, and convert scattered experiments into structured intelligence, the limits that once slowed progress can become the very conditions that accelerate it.

Because when materials are scarce, energy is intermittent, and purity is uncertain, the most valuable resource left is not a chemical—it is knowledge that does not get lost.