Why Process Chemistry Matters More Than Molecules in India’s Agrochemical Industry

India’s agrochemical strength is often described through molecules—active ingredients, synthesis routes, patents, and regulatory approvals. That framing is convenient. It is also incomplete.

In practice, molecules rarely fail India’s agrochemical industry.

Processes do.

What separates India’s most capable chemical manufacturers from the rest is not the novelty of their chemistry, but their ability to stabilise, repeat, and integrate chemistry across scale, geography, and time. The real competitive advantage lives in the space between reactions—where variability appears, decisions accumulate, and knowledge either compounds or quietly disappears.

This is the difference between discovering chemistry and owning it.

The misconception: that molecules determine success

A molecule can be perfect on paper and unreliable in reality. In agrochemicals and pigments, performance is not dictated by structure alone—it emerges from how that structure is produced, handled, formulated, stored, and finally deployed.

In India, this complexity is amplified. Integrated chemical manufacturers operate across chlor-alkali, intermediates, actives, pigments, and formulations, often within the same corporate system. Each unit introduces new chemical interactions, new impurity paths, and new constraints.

This is why Indian chemical leadership has never been molecule-led. It has always been process-led, even when that truth is rarely stated outright.

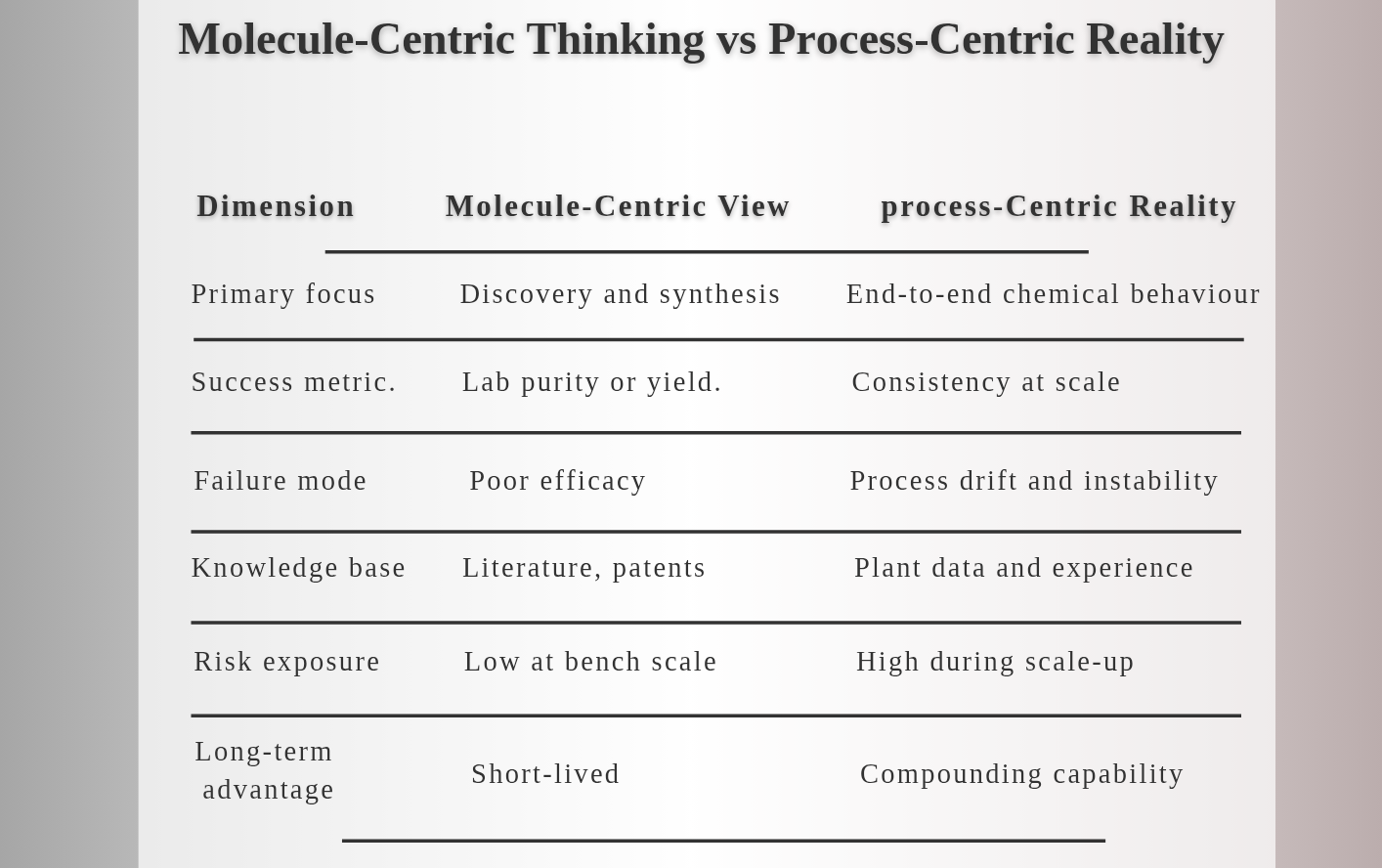

What this table reveals:

India does not struggle because it lacks chemistry. It struggles when process knowledge fails to scale with the chemistry.

Integration multiplies chemistry, not capacity

Large Indian chemical manufacturers are deeply integrated by necessity, not design preference. Chlorine generated upstream must be consumed downstream. Intermediates feed multiple product families. Pigments and agrochemicals share solvents, utilities, and infrastructure.

This integration does not simplify operations—it multiplies chemical dependencies.

A marginal impurity tolerated in an intermediate can destabilise a formulation months later. A minor change in solvent recovery efficiency can alter dispersion behaviour in the field. A reactor geometry difference between plants can subtly change heat transfer and reaction selectivity.

These failures are rarely dramatic. They appear as inconsistency, drift, delayed instability, or unexplained field complaints. And they almost always trace back to untracked process variation, not incorrect chemistry.

Formulation is where chemistry meets reality

In agrochemicals, formulation is not a finishing step. It is where laboratory chemistry collides with environmental reality.

Products must survive monsoon humidity, long transport cycles, variable dilution water, and inconsistent application practices. Stability, dispersibility, wetting behaviour, and shelf life are not guaranteed by molecular design—they are engineered through formulation chemistry.

What determines success is not whether a formulation works once, but whether it works reliably across thousands of batches and millions of hectares. That reliability depends on understanding how surfactants, solvents, stabilisers, and actives interact under real-world stress.

This understanding is built slowly, through iteration. And it is easily lost.

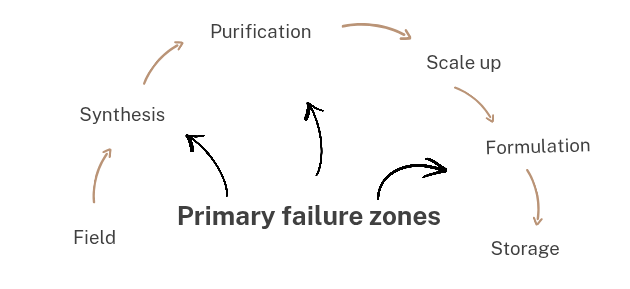

Failures cluster where chemistry meets scale, time, and environment—not at discovery.

Pigments tell the same story, more quietly

Pigment manufacturing reinforces the same truth. Colour is not a molecule—it is an optical outcome governed by particle size distribution, crystal morphology, surface chemistry, and dispersion behaviour.

Two pigment batches can meet identical specifications and behave differently in application. The difference often lies in crystallisation history, washing efficiency, milling conditions, or aging time—parameters that are rarely captured with sufficient resolution.

Again, the limitation is not chemical competence. It is knowledge continuity.

The silent enemy: knowledge attrition

Indian chemical companies are rich in experiential expertise. That strength becomes a vulnerability when:

knowledge lives in individuals rather than systems

experimental rationale is undocumented

process deviations are “understood” but not recorded

scale-up lessons remain anecdotal

The result is not immediate failure, but cyclical rediscovery—the same problems solved repeatedly, the same experiments rerun under new names.

This is not inefficiency. It is strategic leakage.

Where ChemCopilot fits — structurally, not superficially

ChemCopilot does not attempt to replace chemists or automate discovery. Its value lies elsewhere: giving chemistry a memory.

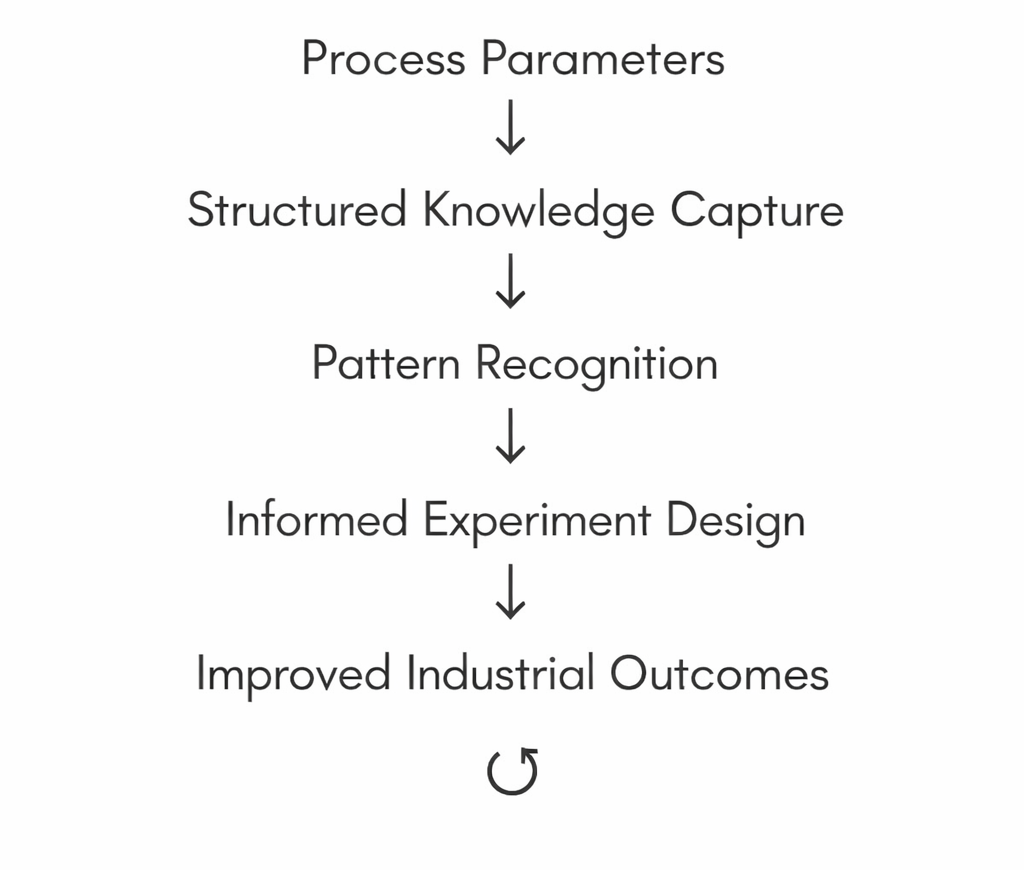

By structuring formulation logic, process parameters, and experimental outcomes into a coherent system, ChemCopilot enables teams to:

retain decision rationale alongside results

correlate process variables with downstream performance

recognise patterns across batches, plants, and products

design experiments informed by history, not guesswork

When a solvent source changes, the system remembers what shifted last time.

When a formulation drifts, the context is already there.

When people move on, the knowledge does not.

The Compounding Intelligence Loop

Without this loop, learning resets.

With it, advantage compounds.

The aggressive truth

India’s agrochemical leadership will not be determined by who discovers the next molecule. It will be determined by who controls variability at industrial scale.

The future belongs to organisations that treat process chemistry as a strategic asset, formulation as an engineering discipline, and knowledge as infrastructure.

Those who rely on intuition will survive.

Those who systematise intelligence will dominate.

ChemCopilot exists for the latter.