Why Do Your Results Change Even When You Do Everything Right?

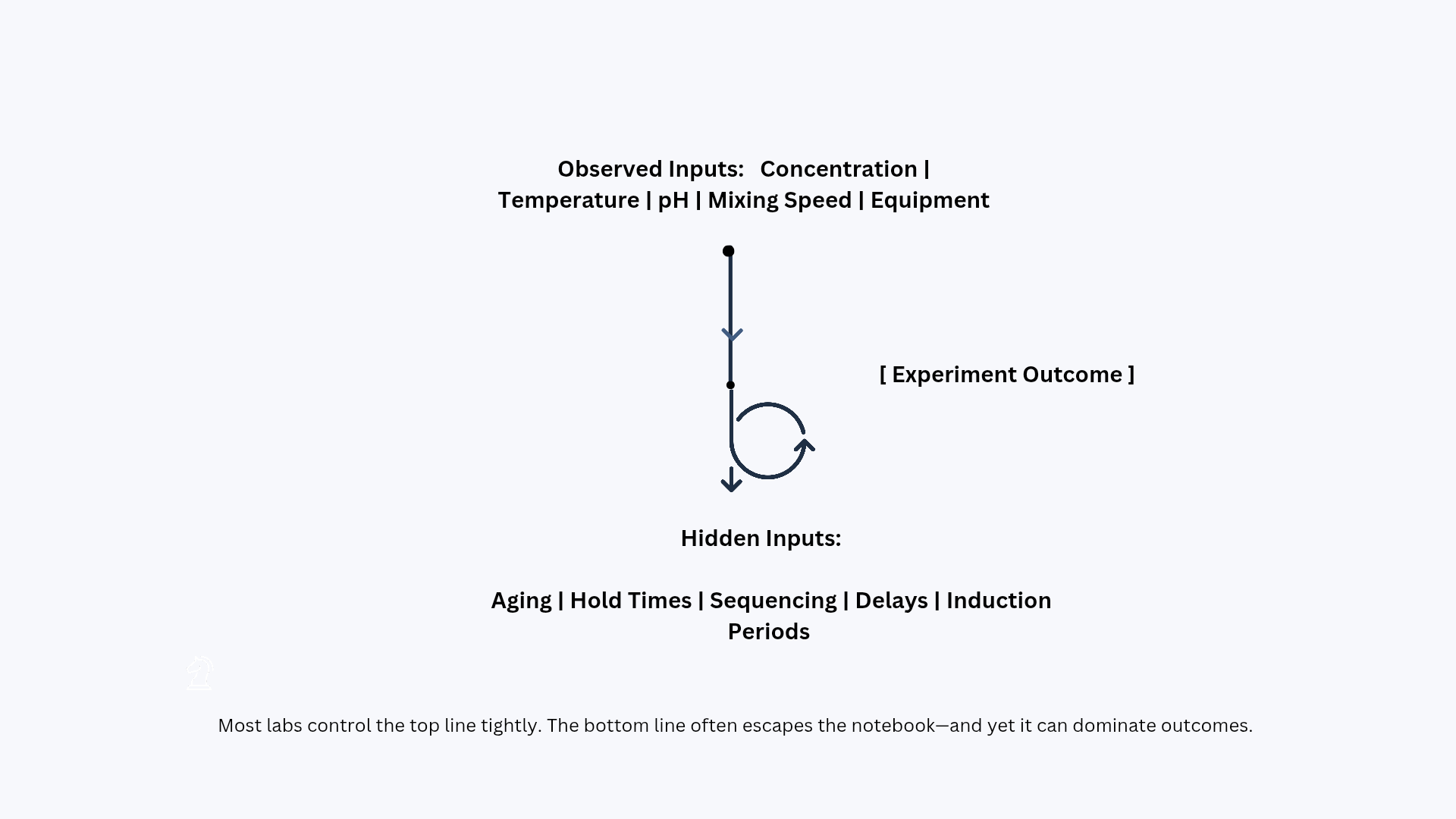

In most laboratories, experimental documentation is built around things—reagents, concentrations, temperatures, instruments, and step-by-step procedures. Yet, many of the most decisive variables in chemistry are not objects or settings at all. They are temporal events: how long a solution was allowed to equilibrate, how long a polymer was left to age before testing, whether a catalyst was exposed to air for three minutes or thirty, or whether a work-up happened immediately or after an unplanned delay. Time rarely appears as a first-class parameter in experimental records, and when it does, it is often captured vaguely—“stirred overnight,” “kept for some time,” “aged,” or “left standing.” These phrases sound harmless, but they can be the difference between a robust, scalable result and an irreproducible anomaly. In modern chemical development—where labs aim to move from bench-scale curiosity to validated, repeatable processes—time is not background noise; it is an active reagent.

A striking paradox exists in scientific practice: researchers know that kinetics governs chemical reality, yet experimental reporting frequently treats time as an afterthought. The result is a hidden dimension of variability that silently accumulates across runs. Consider a formulation scientist who prepares two batches with identical compositions and mixing speeds, but one batch is tested immediately while the other is tested after 48 hours. If viscosity increases due to polymer chain relaxation, partial crystallization, solvent redistribution, or microstructural reorganization, the second batch behaves like a different material altogether—without any “chemical change” being intentionally introduced. The lab record may show no differences, but the material remembers. That memory is written in time.

Time as an Invisible Variable: The Chemistry That Continues After “Completion”

Many experiments do not truly “finish” when the visible step ends. Even after a reaction is quenched or a mixture looks uniform, chemical systems continue to evolve through slow processes: diffusion, reorientation, phase separation, oxidation, hydrolysis, rearrangements, or aggregation. In catalysis, for example, an active species may form gradually through induction periods, while catalyst deactivation may occur subtly through ligand dissociation or poisoning. In colloidal systems, particle size distributions can drift through Ostwald ripening. In emulsions, droplet coalescence and creaming may proceed over hours. In polymers, post-curing and physical aging can shift mechanical properties in ways that are dramatic yet deceptively “quiet.”

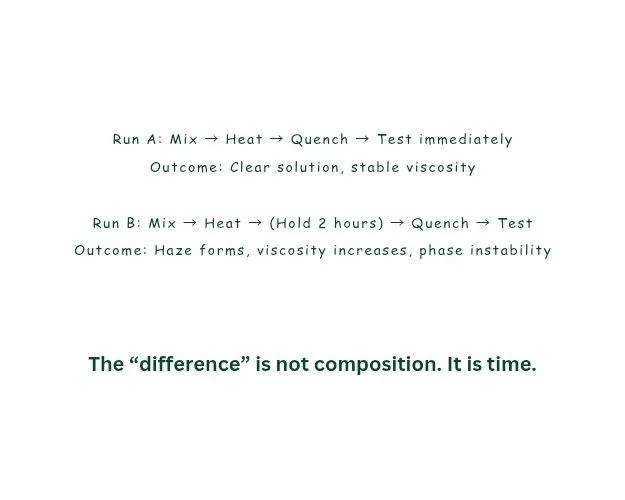

This is why two labs following the same protocol can report conflicting results even when both are competent and careful. The difference may not lie in the recipe—it may lie in the timeline. A brief pause during transfer, a delay while a centrifuge becomes available, an extended hold at room temperature due to scheduling, or a slightly different order of addition can place the system on a different kinetic path. Chemistry is not only governed by state variables; it is governed by history. The system’s present behavior often depends on the path taken to arrive there.

Hold Times, Sequencing Effects, and the “Order-of-Addition Problem”

In practice, time appears in three forms that are rarely documented rigorously:

1) Aging (material evolution with storage time)

Aging is not only relevant to polymers or pharmaceuticals—it matters in coatings, adhesives, electrolytes, surfactant blends, agrochemical formulations, and even simple salt solutions. Many mixtures appear stable initially but develop microstructures over time that change flow, wetting, reactivity, or stability. A dispersion may become more uniform, or it may slowly flocculate. A crystallizing system may remain supersaturated for hours before suddenly nucleating. If a team records only “prepared solution” and not “tested after X hours,” the dataset becomes scientifically incomplete.

2) Hold times (unplanned delays between steps)

Hold time is the gap between operations: filtration delayed, heating postponed, solvent removal extended, or intermediate stored before the next transformation. These gaps can create unexpected side reactions, moisture uptake, oxidation, or slow rearrangements. In process chemistry, hold-time sensitivity can determine whether a synthesis is manufacturable. In formulation labs, it can determine whether a product is shelf-stable or unpredictable.

3) Sequencing effects (the order in which steps occur)

Order-of-addition is often treated as a procedural detail, but it is actually a mechanistic lever. Adding a base into an acidic mixture is not the same as adding acid into base; adding a surfactant before a salt is not the same as adding salt before surfactant. The system may cross critical micelle concentrations, precipitation thresholds, or solubility boundaries at different moments, generating different microstructures. Even when final compositions match, the pathway can lock in differences that persist—especially in non-equilibrium materials like gels, emulsions, and particle dispersions.

Why Traditional Lab Notes Fail to Capture Temporal Truth

Laboratory notebooks were designed for human readability, not for scientific traceability at scale. A researcher can write “stirred overnight” and feel confident that the meaning is clear. But “overnight” can mean 8 hours in one lab and 16 hours in another. “Room temperature” can mean 20°C in an air-conditioned lab and 30°C in a humid monsoon environment. Even the phrase “immediately” is elastic: does it mean within 10 seconds, 2 minutes, or after finishing another task?

This vagueness becomes dangerous when teams attempt to reproduce results months later, transfer protocols between sites, or scale up from lab to pilot plant. The absence of precise timestamps makes it impossible to reconstruct the experimental timeline. Even when time is recorded, it is often scattered across emails, instrument logs, and memory rather than embedded as structured experimental metadata. The experiment becomes a story rather than a dataset.

There is also a cultural reason time goes undocumented: it feels mundane. Researchers prioritize variables that seem “chemical” and ignore those that feel “operational.” But in real-world chemistry, operational conditions are chemical conditions. A formulation that tolerates timing variation is robust; a formulation that collapses under small delays is fragile. The difference matters scientifically and commercially.

The Scientific Consequences: Reproducibility, Scale-Up, and False Negatives

Time blindness generates three recurring failures in R&D:

Reproducibility collapse:

A result cannot be repeated because the original success depended on an undocumented aging period, a specific induction time, or an accidental delay that created the “right” microstructure.

Scale-up surprises:

Bench experiments often proceed quickly, while pilot-scale operations introduce longer transfer times, larger thermal gradients, and extended hold periods. If time sensitivity is unknown, scale-up becomes a gamble.

False negatives in screening:

A catalyst or formulation may appear ineffective because it was evaluated too early—before activation, equilibration, or maturation. The candidate is discarded not because it fails, but because it was not given the correct temporal window.

Where Time Dominates: Real Systems That “Remember”

Some chemical systems are particularly sensitive to temporal variables, and they appear across industries:

Polymer solutions and melts: relaxation, entanglement dynamics, post-curing, and physical aging can change rheology and mechanical properties.

Colloids and nanoparticles: aggregation, ripening, and surface chemistry drift can alter optical properties, catalytic activity, and stability.

Emulsions and dispersions: droplet size distributions evolve; surfactant rearrangements change stability profiles.

Crystallization-driven systems: nucleation is probabilistic and time-dependent; supersaturation can persist before sudden transformation.

Catalytic reactions: induction and deactivation periods can distort kinetic interpretation.

Electrochemical and battery formulations: electrolyte aging, SEI formation behavior, and moisture sensitivity create strong time effects.

Time sensitivity is not a niche problem. It is a general feature of chemical matter.

A Research Mindset Shift: Treat Time Like a Controlled Reagent

To capture temporal truth, labs must treat time with the same seriousness as mass or temperature. That means recording:

exact timestamps for critical steps (start/end times, not vague descriptions),

durations of holds and delays,

order-of-addition with timing gaps,

environmental exposure windows (air, humidity, light),

and time-to-test (how long between preparation and measurement).

This is not bureaucracy—it is scientific clarity. When time is structured, it becomes analyzable. Patterns emerge. Hidden dependencies become visible. And robustness can be engineered rather than hoped for.

How ChemCopilot Can Help Address the “Time Problem” (Without Burdening Scientists)

ChemCopilot is not meant to be “just another digital lab notebook.” The deeper opportunity is to treat time as a first-class experimental variable—capturing it consistently, structuring it in a usable format, and making it easier for teams to learn from it. In most labs, temporal information already exists in fragments: instrument run logs, file creation timestamps, batch IDs, scattered notes, and human memory. The challenge is that this information is rarely unified into a single, interpretable experimental timeline.

ChemCopilot can be positioned as a system that helps labs reduce time-related ambiguity, so researchers can spend less effort reconstructing what happened and more effort understanding why outcomes differ.

1) Supporting Timeline-Based Experiment Recording (Instead of Vague Prose)

Many experimental failures are not caused by wrong ingredients, but by missing context—how long something sat, when it was measured, or what step was delayed. A platform like ChemCopilot can encourage researchers to record experiments as time-ordered events, rather than loose narrative paragraphs.

Instead of relying on phrases like “stirred overnight” or “kept for some time,” the workflow can support capturing key time anchors such as:

mixing start and stop times

heating and cooling durations

hold times between steps

time-to-test intervals

storage conditions and duration

deviations or interruptions during execution

Even small improvements in timestamp discipline can dramatically strengthen reproducibility—because many time effects are accidental, not intentional.

2) Making Time-Dependent Patterns Easier to Detect Across Runs

When time is captured consistently, it becomes possible to compare experiments not only by formulation and conditions, but by timeline differences. ChemCopilot can be positioned as helping teams notice hidden time dependencies that are otherwise invisible in traditional documentation.

For example, teams may discover patterns like:

phase separation occurring only after a specific time-to-test window

yield dropping when an intermediate is held too long

viscosity stabilizing only after a defined aging period

order-of-addition becoming critical only under certain timing gaps

These are not universal rules—they are system-specific behaviors. But once surfaced, they reduce wasted repeats and accelerate optimization.

3) Building a Structured “Memory” for Aging and Stability Studies

Aging is often treated like an extra check, recorded inconsistently across notebooks, spreadsheets, and scattered files. A platform like ChemCopilot can help teams convert aging into a structured dataset: Day 0 vs Day 1 vs Day 7 performance, tied to defined storage conditions and preparation timelines.

Over time, this creates a valuable internal reference that links:

formulation composition

processing history

time-dependent property drift

stability outcomes

This is especially relevant for coatings, adhesives, emulsions, polymer dispersions, and many industrial formulations where “performance over time” is not a side metric—it is the product.

4) Reducing Scale-Up Risk by Highlighting Hold-Time Sensitivity

Scale-up introduces unavoidable time expansion: longer transfers, slower heating/cooling, larger thermal gradients, and more operational waiting. If a chemistry or formulation is sensitive to hold times, a process that works on the bench may fail at pilot scale—not because the science changed, but because the timeline did.

ChemCopilot can be positioned as helping teams identify time-sensitive steps early, so they can design more robust processes by:

defining acceptable hold-time windows

introducing stabilizing steps when needed

tightening sequencing control for sensitive additions

reducing exposure time to air/moisture/light where relevant

The goal is to move teams from repeating procedures to understanding process behavior, which is what real scalability demands.

A Future-Proof Way to Document Chemistry: From Narratives to Time-Aware Data

Chemistry is becoming increasingly data-driven, but data without temporal context is structurally incomplete. A dataset that captures composition, temperature, and pH while ignoring when each step occurred is like a movie reduced to a single frame—technically real, yet scientifically insufficient. When laboratories treat time as an explicit experimental dimension, they unlock sharper mechanistic interpretation, stronger reproducibility, and faster iteration cycles because variability becomes traceable rather than mysterious.

The most important shift is philosophical: experiments are not only recipes—they are timelines. Every chemical system carries a form of memory, and that memory is written in minutes, hours, and days through equilibration, aging, sequencing effects, and hold-time sensitivity. Capturing this silent dimension does not require turning scientists into scribes. It requires documentation practices—and tools—that make timing easier to record, easier to compare, and easier to learn from.

This is where ChemCopilot can fit meaningfully, without exaggerated claims. ChemCopilot’s role can be positioned as supporting researchers in structuring time-aware experimental records, helping teams reduce ambiguity around delays, order-of-addition, time-to-test, and aging windows. When time is captured consistently, labs gain the ability to explain why outcomes drift, identify hidden dependencies across runs, and build experiments that remain reliable beyond a single bench, a single person, or a single day.

In the end, time is not merely something experiments consume—it is something experiments express. And the laboratories that learn to measure it properly will build chemistry that survives outside the notebook: into scale-up, into manufacturing, and into real-world performance—where reproducibility is not a preference, but a requirement.